Designers often aim for perfection. When we create a feature, we want to refine it over and over until it feels just right. This attention to detail is part of what makes good designers great.

But many of us struggle with knowing when to stop. Design is an iterative process, not a one-time exercise. Teams that wait until a design is “perfect” before shipping often miss the mark—because perfection is subjective, timelines are real, and businesses need to move forward. Instead, we should focus on building consistently, delivering value with each iteration, and clearly defining what’s in and out of scope.

This article explores why designing with constraints is not only practical but powerful—and how I learned this firsthand.

Why There Are Constraints

Internally, every organization deals with limited resources—time, people, and budget. Different teams compete for those resources, so projects must be scoped and prioritized within the time available.

Externally, clients and stakeholders may operate within business models and technical environments that cannot immediately support certain design features. Requirements can change, infrastructure may lag behind, and products need to align with operational realities.

Why Constraints Are Necessary

Rather than seeing constraints as limitations, designers and teams should view them as enablers, because:

- They frame the problem clearly and prevent overwhelm.

- They promote flexibility and creativity—designers must find effective solutions within realistic boundaries.

- They support consistent delivery by discouraging over-investment in details that may not align with user or business needs.

- They reinforce a culture of iteration that helps organizations move faster, test sooner, and improve over time.

A Real-world Example

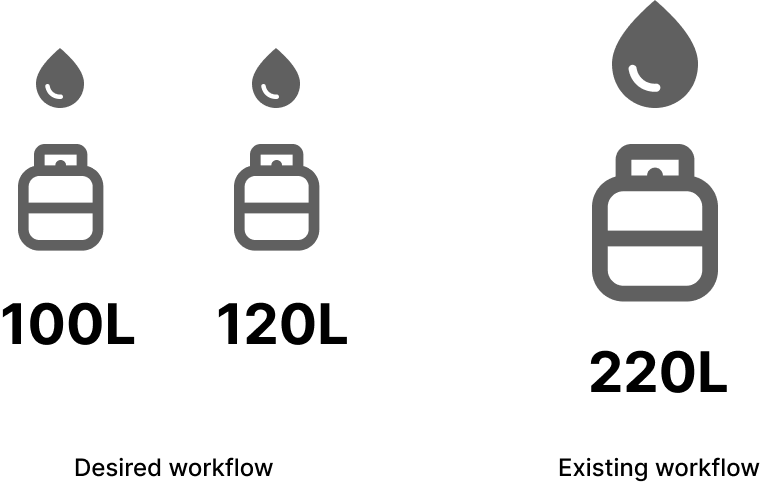

Recently, I was tasked with designing a fuel delivery report feature. One core challenge was how to handle customers with multiple fuel tanks.

From our research—interviews, field observations—we learned that being able to track refueling amounts per tank would help clients better manage inventory, plan deliveries, and identify usage trends.

However, we discovered a gap between the ideal experience and current operations. Our clients didn’t yet have a system in place to uniquely identify each tank. Operationally, they only tracked the total amount delivered.

On top of this, implementing the ideal feature would require significant codebase changes—too risky and complex to complete before our next shipment deadline.

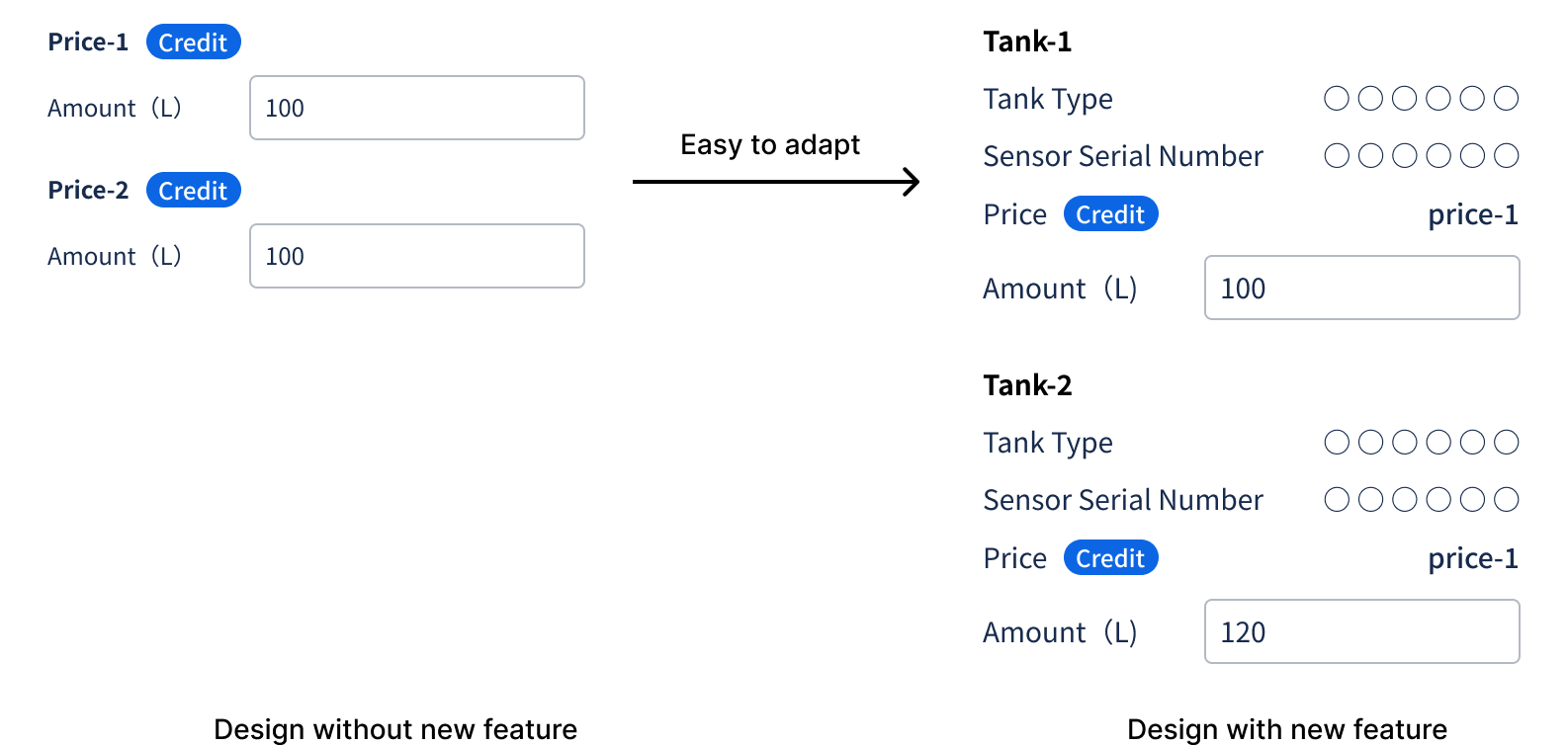

In response, I proposed a design that:

- Matches current workflows

- Builds directly on our existing design system

- Allows easy adaptation in the future

This approach ensured that we could ship a usable feature now and layer on the tank-tracking enhancement when the client was ready. It was a future-proof solution—designed to work today and scale tomorrow, with minimal disruption.

Conclusion

As designers, we’re trained to polish and perfect. But one of the most valuable skills we can build is knowing when to stop. Shipping early and often, within constraints, creates room to learn and improve.

Constraints aren’t obstacles—they’re tools. They guide our decisions, focus our work, and align our process with business objectives. By embracing them, we help our teams move faster and our designs make a real-world impact.